Cervical Cancer Awareness Month

The quiet story of vulval and pelvic skin after treatment

Why we need to talk about life after cervical cancer

January is recognised as Cervical Cancer Awareness Month in many countries, including across Australian organisations that promote HPV vaccination and cervical screening. It is a reminder that most cervical cancers are now preventable with HPV vaccination and regular tests, and that early detection saves lives.

What we hear far less about is what happens after treatment, especially for women over 40 who are already dealing with perimenopause or menopause.

For cervical and other gynaecological cancers, treatment often involves some combination of:

- Surgery (for example cone biopsy, trachelectomy or hysterectomy)

- External beam pelvic radiotherapy

- Internal brachytherapy

- Chemoradiation

These treatments are life preserving. They also have long term effects on the skin and mucosa of the pelvis, vulva and vagina that are rarely discussed outside specialist rooms.

Many women describe:

- Burning or stinging with sitting or walking

- Pads, seams and synthetic underwear that suddenly feel like sandpaper

- Pelvic examinations that are intolerably painful

- Sex that feels impossible, not just uncomfortable

This Skin Edit is about that quieter side of survivorship. It is written for women 40 plus who have been through treatment for cervical or other pelvic cancers, as well as those who support them.

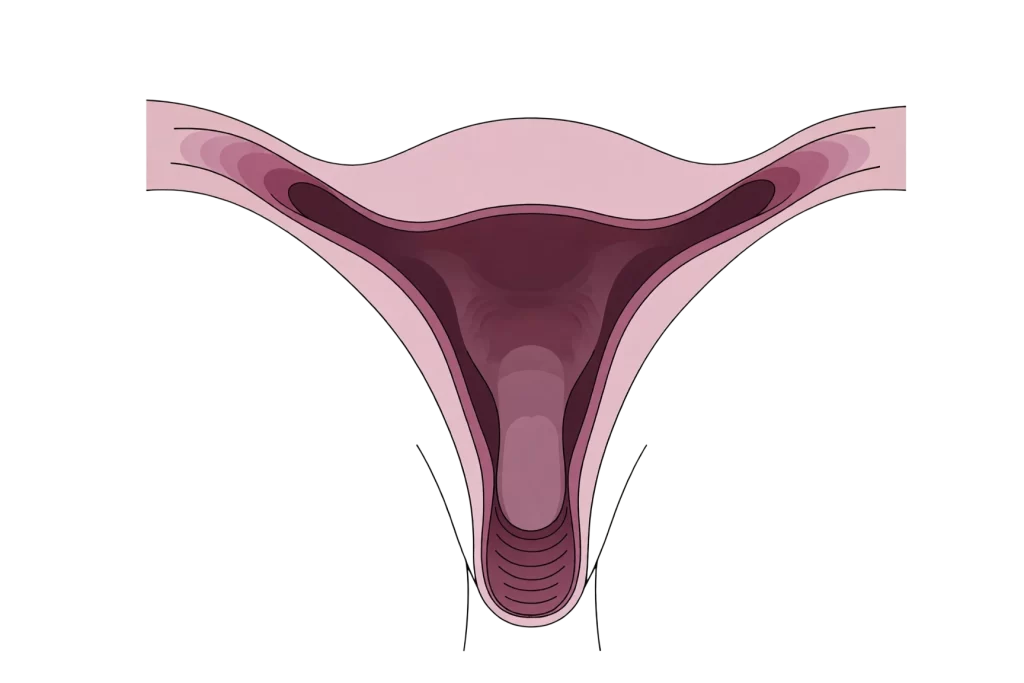

What pelvic treatment actually does to tissue

Pelvic radiotherapy is highly targeted, but it cannot avoid all healthy tissue. Reviews of late effects show that radiation to the pelvis can affect the vagina, vulva, perineum, bladder, bowel and pelvic bones, with both short term and late toxicities.

Common late effects reported in women after pelvic radiotherapy for cervical and uterine cancers include:

- Vaginal dryness and atrophy

The vaginal lining becomes thinner, less elastic and less well lubricated. - Vaginal stenosis

Narrowing or shortening of the vaginal canal due to scar tissue. This can make speculum examinations and penetrative sex painful or impossible. - Fragile mucosa

The tissues may bleed more easily with minor trauma or friction. - Changes to surrounding skin

The vulval and perianal skin can become drier, more prone to irritation and slower to repair if rubbed, as well as more sensitive to soaps, perfumes and sanitary products.

Alongside this, many women will be in a low oestrogen state due to surgical menopause, radiotherapy impact on the ovaries, or endocrine therapies. Low systemic oestrogen itself is known to contribute to genitourinary syndrome of menopause, with thinning of vulval and vaginal epithelium, reduction in natural lubrication and changes to the microbiome.

So you have two forces acting together:

- Tissue that has been injured, healed and scarred by cancer therapy

- Tissue that is also undergoing hormone related atrophy

The result is a pelvic region that behaves very differently under everyday mechanical load.

Friction, not fussiness

Women often tell clinicians they feel like they are being fussy, or that they should just be grateful to be alive.

From a mechanical point of view, you are not being fussy. You are living in a body where:

- The mucosa is thinner, with less blood flow and fewer glands

- The collagen and elastin that used to give stretch have been disrupted by radiation and scarring

- The barrier lipids and microbiome that used to protect the surface are altered

- There is less natural lubrication from both local glands and oestrogen driven secretions

Studies on late pelvic radiotherapy effects highlight the combined impact of vaginal dryness, stenosis and atrophic vaginosis on sexual function and examination tolerability.

When you then add everyday friction:

- Seatbelts and car journeys

- Sitting at a desk all day

- Sanitary pads, panty liners or incontinence products

- Standard underwear seams or shapewear

- Bicycle or horse riding saddles

- Penetrative sex or even insertion of a speculum

the same mechanical force now produces a much higher “dose” to tissues that are thinner, drier and more fragile.

What used to be mild rubbing can now result in:

- Micro tears and fissures

- Burning or stinging that continues for hours

- Bleeding spots on toilet paper or underwear

- A strong urge to avoid any future contact

Recognising this as friction on changed tissue rather than personal weakness is often the turning point in care. It opens the door to mechanical and skincare solutions, not just “put up with it”.

Evidence based non hormonal options

Hormone therapy is not suitable for everyone, particularly for women with hormone sensitive cancers or those advised to avoid systemic oestrogens. For these women, guidelines and reviews consistently recommend non hormonal vaginal moisturisers and lubricants as first line for genitourinary symptoms.

Within that group, hyaluronic acid based products have attracted particular interest.

- A review of non hormonal treatments for genitourinary syndrome of menopause notes that hyaluronic acid based moisturisers have shown promising clinical results both in healthy women and in cancer survivors who cannot use hormones.

- A clinical study in women receiving pelvic radiotherapy found that a low molecular weight hyaluronic acid preparation combined with vitamins helped reduce vaginal atrophy scores, inflammation and patient reported vaginal toxicity compared with controls.

- Further work has explored hyaluronic acid gels and ovules as adjuncts to reduce acute and subacute radiotherapy related vaginal side effects, although study sizes are still relatively small and formulations vary.

Other non hormonal options include:

- Simple emollient creams and oils for external vulval skin

- Silicone or water based lubricants for intercourse or dilator use

- Vaginal moisturisers with different polymer bases and osmolarities

The important points are:

- These products are supportive, not curative. They aim to improve hydration, comfort and elasticity of the tissue, not to treat cancer or reverse all damage.

- They need to be selected with your oncology and gynaecology team, especially if you have had recent treatment, active disease, ulceration or a history of severe mucosal toxicity.

- They work best as part of a wider plan that includes mechanical strategies and, where appropriate, pelvic floor physiotherapy and psychosexual support.

Some modern intimate formulations use hyaluronic acid in microsphere or matrix systems, designed to hold water and release it gradually at the mucosal surface. This can help maintain moisture over time without heavy occlusive films, which is particularly relevant for fragile, post radiotherapy tissue. This is a concept that aligns well with V.supple’s science led focus on microsphere technology, although specific choices must always be guided by the treating team.

Everyday strategies that can reduce friction load

Clinical trials sit on one side of the story. On the other side is the daily reality of sitting, walking, working and being intimate in a changed body.

The following strategies will not apply to everyone, but they can be a useful conversation starter with your care team.

1. Fabrics and seams

- Choose underwear with cotton rich, breathable gussets, soft waistbands and minimal internal seams at the groin.

- If you use pads or liners for discharge, spotting or incontinence, trial brands with a cotton top sheet and avoid fragranced variants.

- For work clothes, consider looser cuts around the pelvis to reduce continuous pressure on the vulval and perineal area.

2. Washing and grooming

- Use lukewarm water rather than hot, and avoid soaps or washes on the vulval area. If a cleanser is needed, choose one formulated for sensitive skin, free from fragrance and harsh surfactants.

- Pat dry rather than rub. A soft cloth or tissue pressed gently against the area is kinder than a rough towel.

- If you remove pubic hair, be aware that this removes a natural friction buffer and can increase irritation. Many clinicians advise trimming rather than full removal after pelvic radiotherapy.

3. Position changes and padding

- For long car or plane trips, use a soft cushion or gel pad on the seat and take regular breaks to stand and move.

- If seatbelts or bike saddles press on irradiated areas, occupational therapists and continence physiotherapists can help with specific padding solutions.

4. External barrier support

- Apply a thin layer of a simple, fragrance free emollient or barrier cream to high friction zones (inner thighs, under the buttock fold, perianal skin, external vulva) before predictable triggers such as long walks or social events.

- If you are trialling any new product, patch test on an intact area of skin first and stop immediately if there is stinging, burning or rash.

5. Dilators, examinations and sex

Guidance for vaginal stenosis prevention and management commonly includes dilator use and sexual activity, but recent trials highlight that evidence for routine dilator use is mixed and practice is evolving.

What is clear is that:

- You are entitled to pain relief and topical comfort measures for pelvic exams.

- You can ask for smaller specula and more time.

- You should never feel pressured into penetrative sex if it is painful or distressing.

Pelvic floor physiotherapists and psychosexual therapists with oncology experience can help build a graded plan if you wish to work towards tolerating examinations or intercourse again, but it must be at your pace.

Preparing for your next appointment

Many survivors minimise symptoms because they do not want to appear ungrateful or to take up clinic time. Yet long term studies show that urinary, bowel, sexual and pelvic discomfort after pelvic radiotherapy have a major impact on quality of life.

Before your next review, it can help to write down:

- The three most troubling symptoms related to your pelvic or vulval region

- How often they occur, and what triggers them (for example sitting, pads, intercourse, walking)

- What you have already tried, and what has or has not helped

Useful phrases include:

- “I am grateful for the treatment, and I am also struggling with…”

- “I would like to understand what is safe for me to use on my vulval and vaginal tissue now.”

- “Is there a pelvic floor physiotherapist or sexual health clinician you recommend for survivors like me”

If bringing a partner feels supportive, you can brief them beforehand so they understand that this is about your comfort and function, not just intimacy.

When to seek urgent review

Although much of the discomfort after treatment is due to chronic changes, some symptoms warrant urgent medical attention:

- New or increasing vaginal, rectal or urinary bleeding

- New lumps, ulcers, foul smelling discharge or visible tissue changes

- Severe pain, fever or difficulty passing urine or stools

- Sudden changes in continence

Radiotherapy can make blood vessels and mucosa more fragile, so bleeding can appear months or years later.

However, new bleeding should always be assessed to rule out recurrence, new pathology or other causes.

Trust your instinct. If something feels wrong, you are not wasting anyone’s time by asking for help.

You are not difficult, you are living in a different body

Cervical Cancer Awareness Month is often framed around prevention and early detection, and those messages matter.

But for the woman who has already been through treatment, the awareness that may mean the most is this:

- It is valid to grieve the changes to your pelvic and vulval tissue.

- It is reasonable to seek comfort, not just survival.

- It is appropriate to expect your care team to talk about sex, skin, friction and quality of life, not only scans and blood tests.

Your pelvis has carried diagnosis, treatment and healing. It deserves the same scientific attention and everyday kindness that your tumour once received.

Part proceeds to McGrath Foundation

Part proceeds to McGrath Foundation